Overcoming the environmental challenges of our past

Singapore in the 1960s and 1970s was marked by night soil buckets, water rationing, and unhygienic street hawkers.

Workers shovelled refuse from open roadside bin points onto pushcarts, and discarded them at open dumping grounds across the island.

This form of waste collection was irregular and inefficient. In 1964, only around 60% of each day’s refuse was cleared. Refuse often piled up along roads, in back alleys and other common areas. This left streets reeking of decomposing refuse and caused pest problems, both made worse by the hot and humid weather.

The solid waste journey

Our waste management needs started changing from the 1970s. Singaporeans were moving from kampongs to high-rise apartments, and competition for land became more intense as the country developed.

CLEANING UP OUR STREETS THROUGH WASTE COLLECTION

To safeguard public health and avoid disease outbreaks, we had to devise an organised waste collection system.

This prompted the formation of the Ministry of Environment (ENV) in 1972, now called the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (MSE).

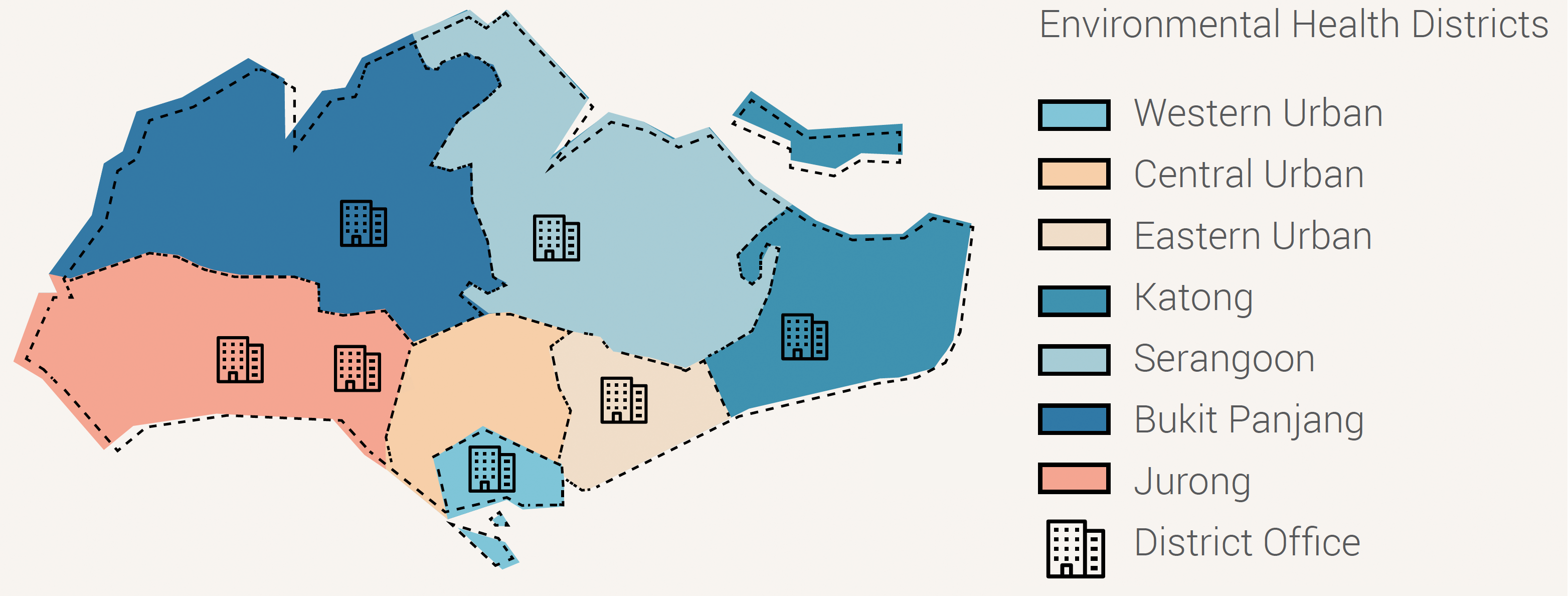

A district-based solid refuse collection system was set up. Daily refuse collection services for domestic and trade premises started operating from seven district offices, and refuse collection fees were paid through household utility bills. Waste collection vehicles also replaced pushcarts, making collection faster and less strenuous for workers.

DOWN THE CHUTE TO CLEANLINESS – TEACHING SINGAPORE TO “BAG IT”

As Singaporeans moved from kampongs to high-rise apartments, vertical refuse chutes were introduced as a quick and convenient way to collect refuse from multiple flats.

For public housing flats built up to 1988, each individual flat unit came with a refuse hopper in the kitchen, also known as the Individual Refuse Chute System (IRCS). Waste thrown into each chute would fall into a bin at the bottom (ground level) of the chute. The refuse collection workers would go from chute to chute to collect the refuse from the bins. To combat smell and pest issues from refuse (e.g. food waste) that was directly thrown into chutes, ENV launched educational programmes since 1979 to educate residents to bag their refuse before throwing it down the chute. Educational posters showing the steps for bagging waste were developed and distributed across the island. It took many years for Singaporeans to get it right, but it is a responsible practice that continues till today.

HDB flats built from 1989 have an improved Central Refuse Chute (CRC) system, where flats on each floor shared a common chute with the refuse hopper located near at the lift landing of each floor. The reduced number of chutes in each block of flats saved space and allowed for more efficient refuse collection.

PIONEERS IN TURNING WASTE TO ENERGY

Reducing waste to just one-tenth of its volume while generating electricity sounds like a great way to make the most of our waste.

But this was unimaginable in the 1970s in Singapore.

It was only done in some parts of Europe and Japan, which adopted waste-to-energy (WTE) incineration, where electricity was generated from waste incineration. These WTE plants were also expensive.

But faced with a shortage of land for landfilling, Singapore took a bold step in 1973 to build the first WTE plant in Asia outside of Japan. In 1979, Singapore’s first WTE plant, located at Ulu Pandan, was completed at a cost of $130 million, a hefty investment at the time.

Singapore took a $25 million loan from the World Bank to fund the project, which marked the first time the international financial institution supported the construction of a WTE plant.

Since then, four other WTE plants have been commissioned – Tuas Incineration Plant (1986), Senoko WTE Plant (1992), Tuas South Incineration Plant (2000) and Keppel Seghers Tuas WTE Plant (2009). Together, they incinerate about 7,600 tonnes of waste a day.

By reducing the volume of waste by up to 90%, while generating electricity that is sold to the grid, incineration has been an effective method of waste disposal for Singapore.

While Singapore has achieved our aim of developing a waste management system that has safeguarded public health, we can do more. We can recover valuable materials from waste. This involves a paradigm shift to manage our waste in new, more sustainable ways to deal with our growing resource constraints. Read more about the science behind incineration

https://www.towardszerowaste.sg/zero-waste-masterplan/chapter1/our-past/